In this lecture, we will take a look at the OS side of VM management. We’ll look at how paging is implemented, some policy decisions we can make, and we deal with memory resource management in general. We’ll also look at the user level side, and how applications interact with the operating system to request memory, and leave off with detailed view of a sample VM system.

Paging in day-to-day use

- Demand Paging:

- In day to day use, not all parts of a program application are needed the same time. so, when you launch the program, only the portions of the code and data that are immediately needed are loaded into RAM. Additional pages are brought in as they are required during the program’s execution

- BSS Page Allocation:

- If your program has uninitialized global variables, memory space for these variables is allocated dynamically when the program runs → this involves creating new pages in the process’s address space

- Copy on Write:

-

This is a strategy to optimize memory use. When processes share a resource (like memory), they initially share the same physicla pages. If one process attempts to modify a shared page, a copy of the page is made, and the modification is applied to the copy rather than the original shared page

-

→ Subtopic: Paging

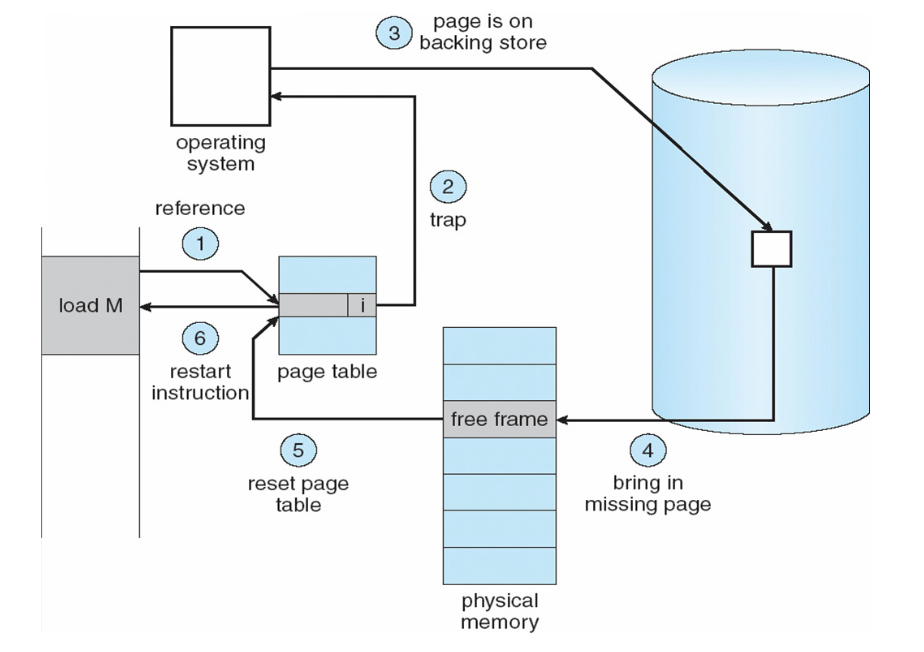

Let’s take a look at the OS’s workflow for paging memory.

-

Here, in step 1, assume on the left, some program loaded some memory address (Load M)

-

The reference in the processor attempts to look up in the page table, to see if the memory exists

- In the diagram, the page table entry is marked invalid

- This will lead to a page fault, trap to the OS in step 2

-

In step 3, the OS realizes the memory is somewhere on disk, so it will allocate a page and read that memory from disk (step 4) to be placed into physical memory (speeds up future access times)

-

Then, once the physical page has been brought in, it can then update the page table, inserting the reference of the correct page and re-start the load M instruction that caused the page fault exception in the first case

On TLB Miss → make reads from memory from page tables(s) to find the translation in the page table, and bring back to the TLB evicting some other entry. Now if not in page tables, or invalid, OS iwll find the memory somewhere on disk, allocate a new page and write the memory to the page and add it to the physical memory (or if in swap space, OS brings the required page from the swap space into a previously allocated page frame in physical memory.) Then, update page table(s) and update TLB.

This process allows us to use more memory than is present on a machine, as we can move memory back and forth between disk → this simulates larger virtual memory than physical memory.

→ Working Set Model

The working set model is a concept in memory management that helps in understanding and managing the dynamic behaviour or a process’s memory usage over time. The working set of a process is defined as the set of pages the process is currently using.The working is particularly relevant for systems that use demand paging and page replacement algorithms.

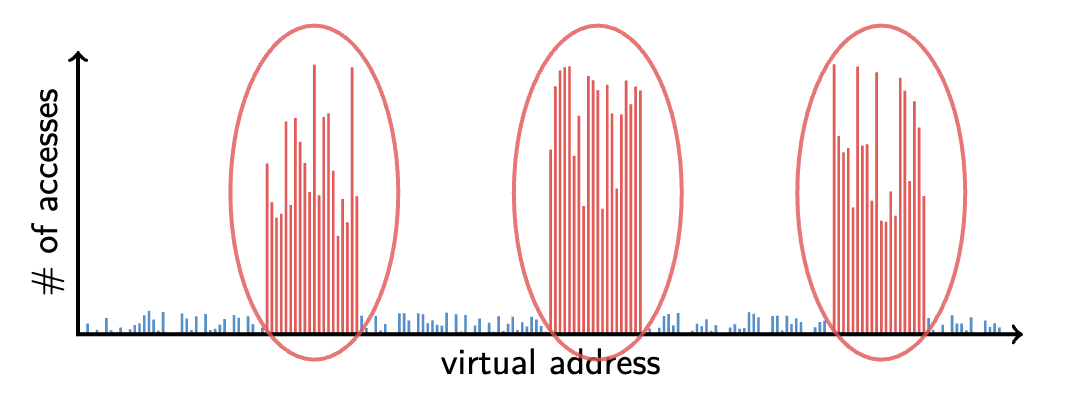

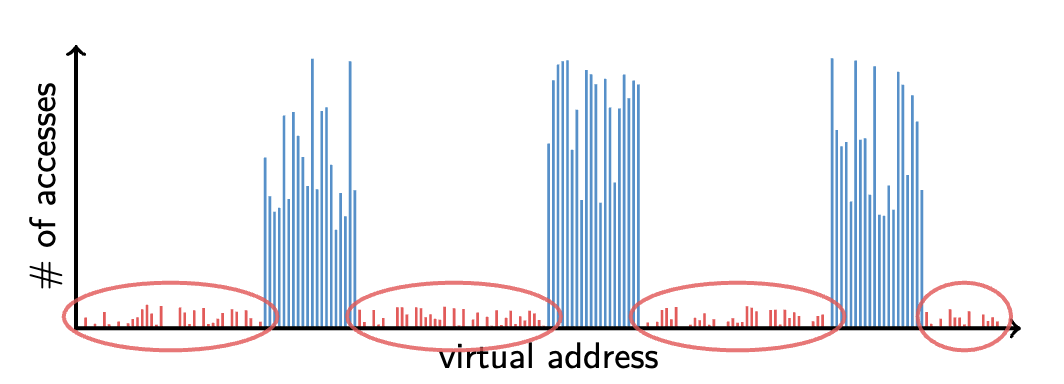

While the mechanism above is fairly straightforward, the problem comes down to the policy decisions we make when implementing memory management. Main problem is Disk or SSD, is much slower than memory (about 1000x times slower). So, there is a certain cost associated with reading and writing to and from disk to service paging requests. We address this issue with 80/20 rule: 20% of memory gets 80% of accesses → the remaining 80% of memory is getting a small amount of accesses (~20%)m and are kept in disk. Consider the below:

-

So, left one shows 20% of memory (small portion of virtual addresses) has 80% of the memory accesses → keep the hot 20% in memory

-

The right one shows 80% of memory (most virtual addresses) have 20% of the access → keep the cold 80% on disk

This introduces one of the main challenges of paging. Namely: How to resume a process after a fault? In particular, we want to know what to fetch from disk and what to evict from RAM

→ Restarting Instructions

The hardware provides kernel with information about page fault. This includes information such as:

- Faulting virtual address (In

%c0_vaddrin MIPS) - Address of instruction that caused fault (

%c0_epc) - Was the access a read or write? Ws it an instruction fetch? Was it cause by user access to kernel-only memory?

The hardware must allow for resuming after a fault. Idempotent instructions are easy to handle.

-

These are instructions that can safely repeated multiple times without causing different effects after the first execution

-

Key idea: Just re-execute any instruction that only access one address

→ What to fetch?

How do we decide on what to fetch?

- At the very least: bring in the page that caused the page fault

- What about pre-fetching surrounding pages?

- Consider fetching not only the page that caused the page fault, but also the neighbouring pages in anticipation of future access

- Reading 2 disk blocks is around the same speed as reading one → constant time difference

- If the application exhibits spatial locality (so, it tends to access data that is close together in memory), it can be advantageous to store and read multiple contiguous pages.

- Pre-Zeroing unused pages in idle loop

-

Unused pages (those for stack, heap) are often pre-zeroes during idle CPU cycles

-

Zeroing pages involves setting all the buts in the memory to 0

-

Zeroing is done during idle time to avoid performance penalties when the pages are actually needed

-

Doing this pre-emptively is preferable, as on demand is slower

-

→ Selecting physical pages to evict/eject

-

After the page fault occurs, we allocate a page and read that memory from disk. We then need to place it into physical memory. We may need to evict some pages (moving them from RAM to disk), and we’ll see more of this later.

-

Essentially, we look through all the memory of an application, and find some pages we believe are cold and swap them to disk

-

There are many problems that occur from this → could affect caching behaviour or how we deal with page tables

-

**A bit of out of topic → here some important things brought up here

→ Superpages

**

- Recall we mentioned that MIPS have multiple page sizes → these are generally called super pages

- These can reduce the overhead of the TLB:

- With larger page sizes, each TLB entry covers a larger memory range → helps reduce the overhead of the TLB

- The TLB really holds page translations → it tells you what the virtual page number maps to (physical page)

- When we want to translate a virtual address, the TLB gives a very quick translation of the first part (VPN) to (PPN). We then concatenate the offset to the end to obtain the address.

- With large page size, for a given mapping, we will be able to translate a larger set of addresses quickly as they are all in the same mapping.

→ Eviction Policies: FIFO eviction

-

Evict oldest fetches page in system

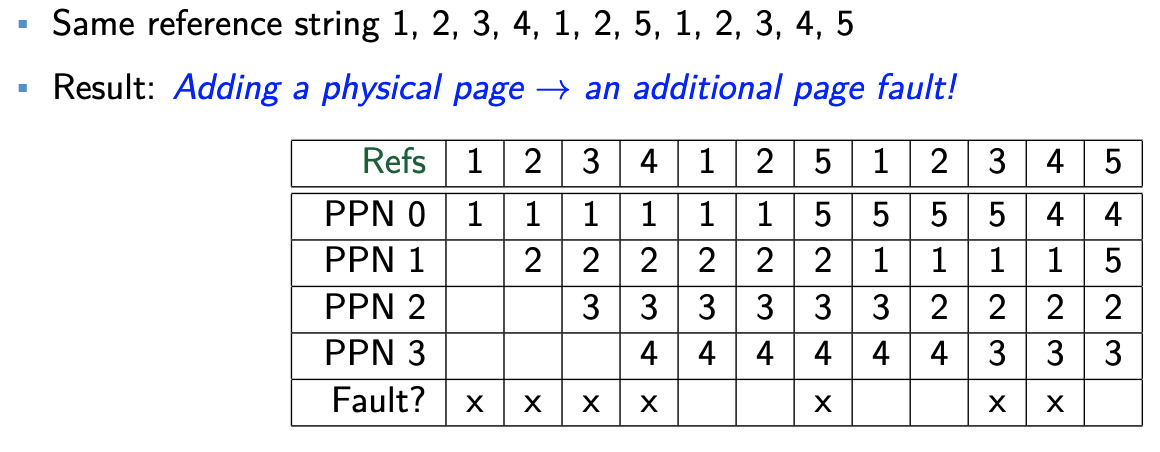

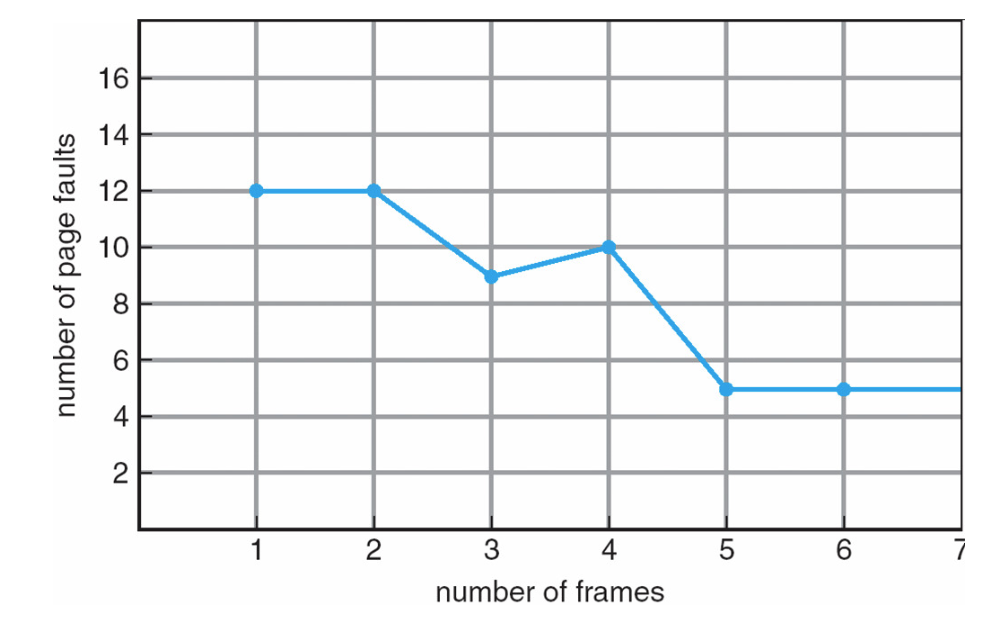

→ Belady’s Anomaly

This tells us that adding more physical memory does not always mean fewer faults. This is shown with the below diagram:

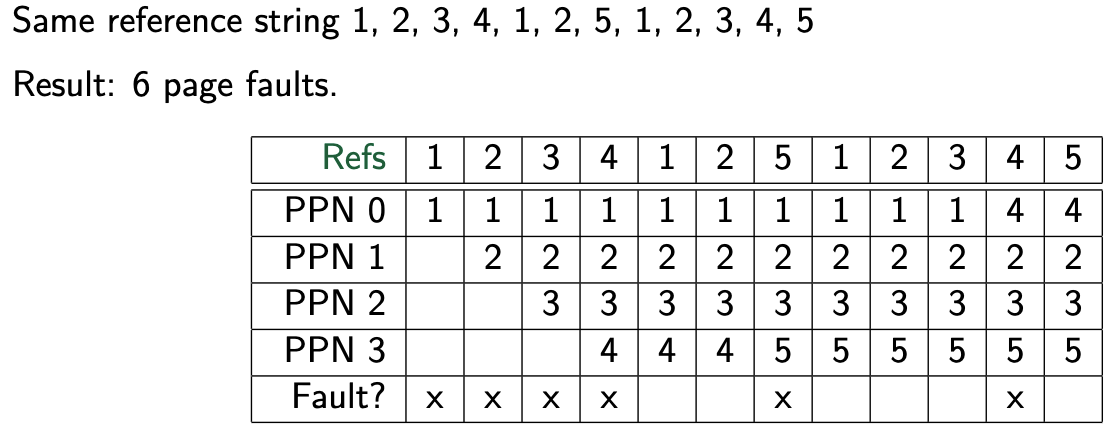

→ Optimal Page Replacement

What is optimal (if you knew the future)? → replace page that will not be used for longest period of time in the future

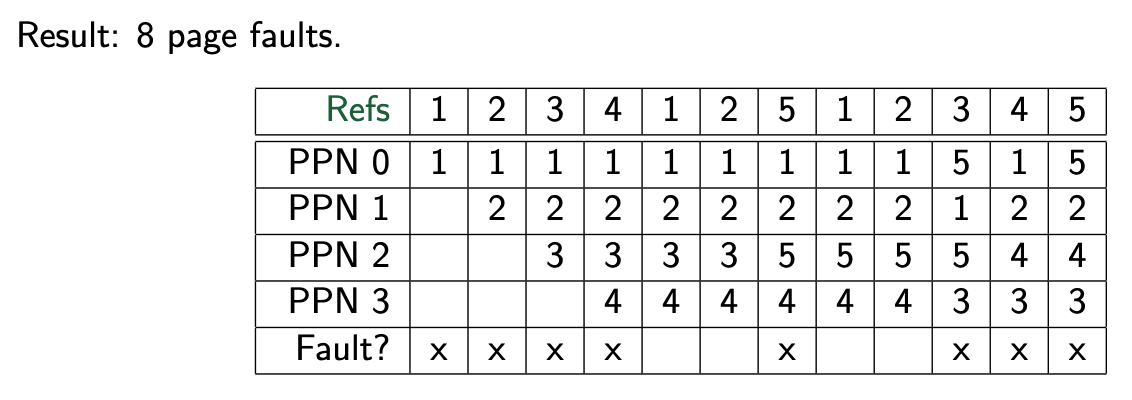

→ LRU Page Replacement

While the optimal page replacement is, well, optimal, we can’t know the future. We approximate optimal with least recently used.

However, LRU has its own issues. For one, it can potentially give the worst result possible, i.e. page fault every time (imagine the next reference is always something not in the TLB). So, how can implement the LRU efficiently?

→ Straw man LRU implementations

The challenge we now consider is how can we implement LRU? Consider the following:

-

Stamp each PTE( Page Table Entry) or TLB entry with a timer value

- Every time we access memory, we potentially need to update the page table entry. This is something that needs to be done on every access

- Then, we would need to sort the pages time stamps → find the oldest counter value which gives us our LRU page

- The problem is → this generates double memory traffic

-

What about maintaining a doubly-linked list of pages?

- On access, remove page and place at tail of list. Finding the page itself may requires us iterating over every entry → again, expensive

-

We don’t need to exactly implement LRU, it is much simpler to design a method that approximates LRU. This brings us to the clock algorithm

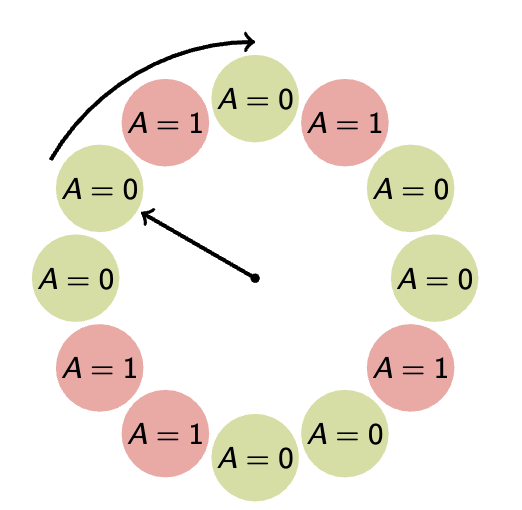

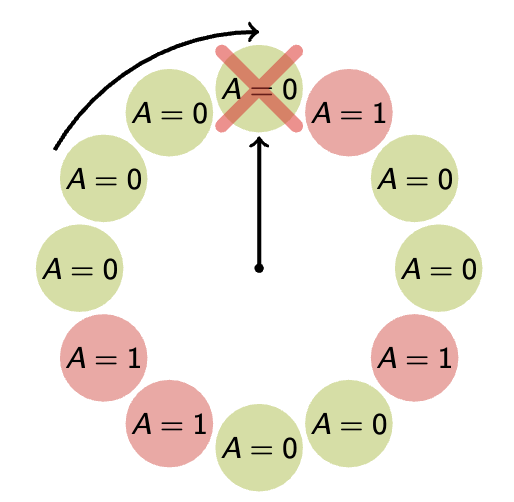

→ Clock Algorithm

This is a page replacement algorithm, and was designed to approximate the behaviour of LRU. Let’s see how it works.

- Recall that in the previous lecture, each page table entry has an accessed bit.

- The clock first linearly scans over all pages in the page table → scanning for access bit, which tells us if the page was accessed recently. The clock algorithm is going to reset that bit to periodically check it has been accessed.

A = 0 means the page has not been accessed, A = 1 means otherwise

The clock algorithm does not end, as in the conventional sense of algorithms — rather, it continually loops. The algorithm keeps the pages in circular FIFO list. The scan looks like:

-

If page’s A bit = 1

-

then set A bit to 0 and skip

-

else if A = 0, evict

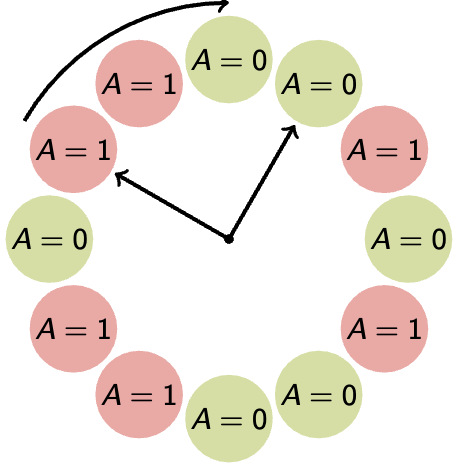

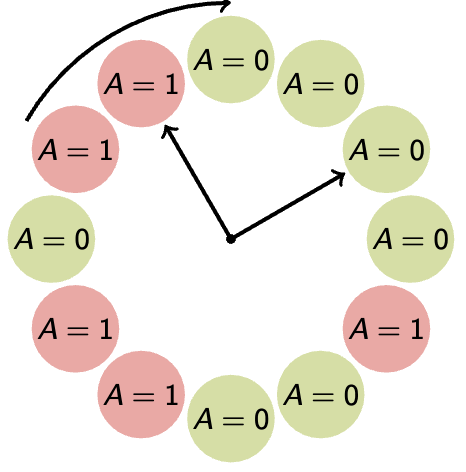

A potential problem is if memory is large, and we have a lot of pages in the page table. In this case, we can add a second clock hand:

- 2 hands move in lockstep → means they move together in synchronization

- The leading hands clears A bits (sets A = 0)

- The trailing hands evicts pages with A = 0

We can also take advantage of the dirty bit:

- Page can be (accessed XOR un-accessed) and (clean XOR dirty)

- Evict clean pages before dirty ones because no write back → evicting dirty pages would require some write to disk

- Or, use -bit accessed count instead of just A bit

-

This allows for a gradient → instead of black and white view of activity, we can see relative access rate of the pages

-

Evict page with lowest count

-

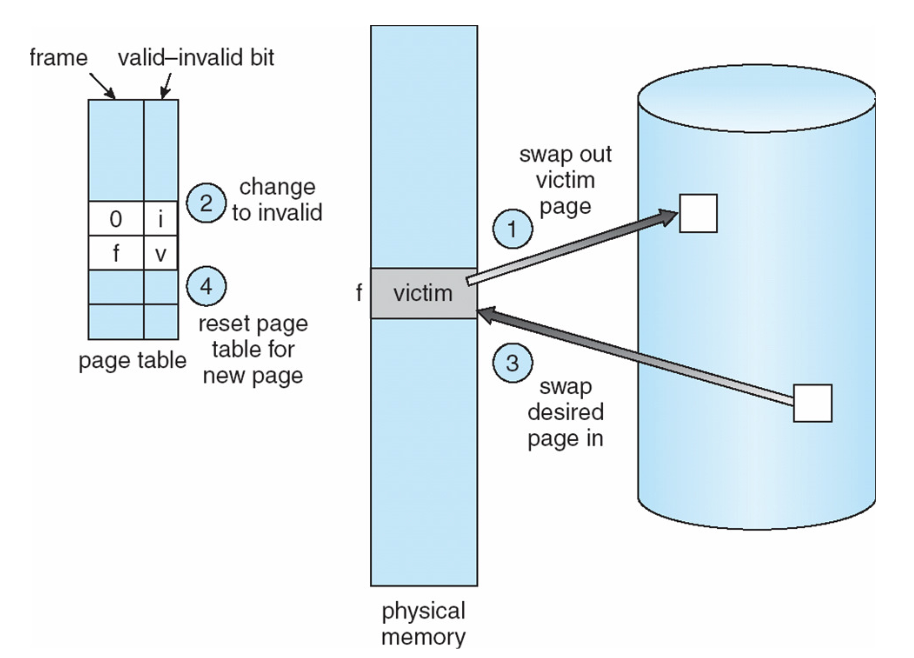

→ Naïve Paging

The below diagram demonstrates another issue with paging:

The above diagram is very self-explanatory:

- Victim page from physical memory is being evicted from some page eviction policy (which was frame 0 a.k.a PPN 0) (1) → so, we mark it as invalid in the page table (2) and swap out to disk

- Once that swap out completes, the desired page, which reads from disk, is swapped into physical memory (3) and update the page table (4)

But in this naive page replacement, there are 2 disk I/Os per page fault. Can we reduce this number?

→ Page Buffering

The idea is to reduce the number of I/O paths on the critical path. With this, on a page fault, we will perform a single I/O operation to read the page in.

- Strategy: Keep a pool of free page frames

- On fault, select a victim page to evict (same as before)

- But now, store page fetched from swap space into already free page from the pool

- Can resume execution while writing out victim page

-

So, we now no longer need to wait for swap out to full finish. We only need to swap into a free page frame, and swap out concurrently while we resume execution

-

→ Page Allocation

A second consideration is whether the page allocation decisions are done globally or locally. Consider the following slide:

Basically, do we use page eviction policies for all pages globally, regardless of which process they belong to, or should we use these policies specific to the process they are from, and perhaps tailor more specific policies based on things like how much memory a process needs, etc.

check the TLB for a mapping

if not in TLB, follow the page table to find the virtual to physical page mapping

bring this mapping into the TLB

bring the page into RAM

addition if there is a page already there, swap it out in to the swapspace