Last lecture, we took our first look at Mutex’s, and how we could prevent certain race conditions without necessarily needing to be in a sequential consistency memory model. With locks, we saw a way of ensuring that mutliple threads would not be able to access a shared resource at the same time as other threads, leading to data races and unpredictable behaviour. Now, we dive deeper and take a look at monitors (not the one on your desk : D)

Monitors

In operating system design, a monitor is a high-level synchronization construct that provides a way to control access to shared resources within a concurrent program. The concept of monitors was introduced by Per Brinch Hansen in the 1970s as a means of simplifying concurrent programming and managing the coordination between multiple processes or threads.

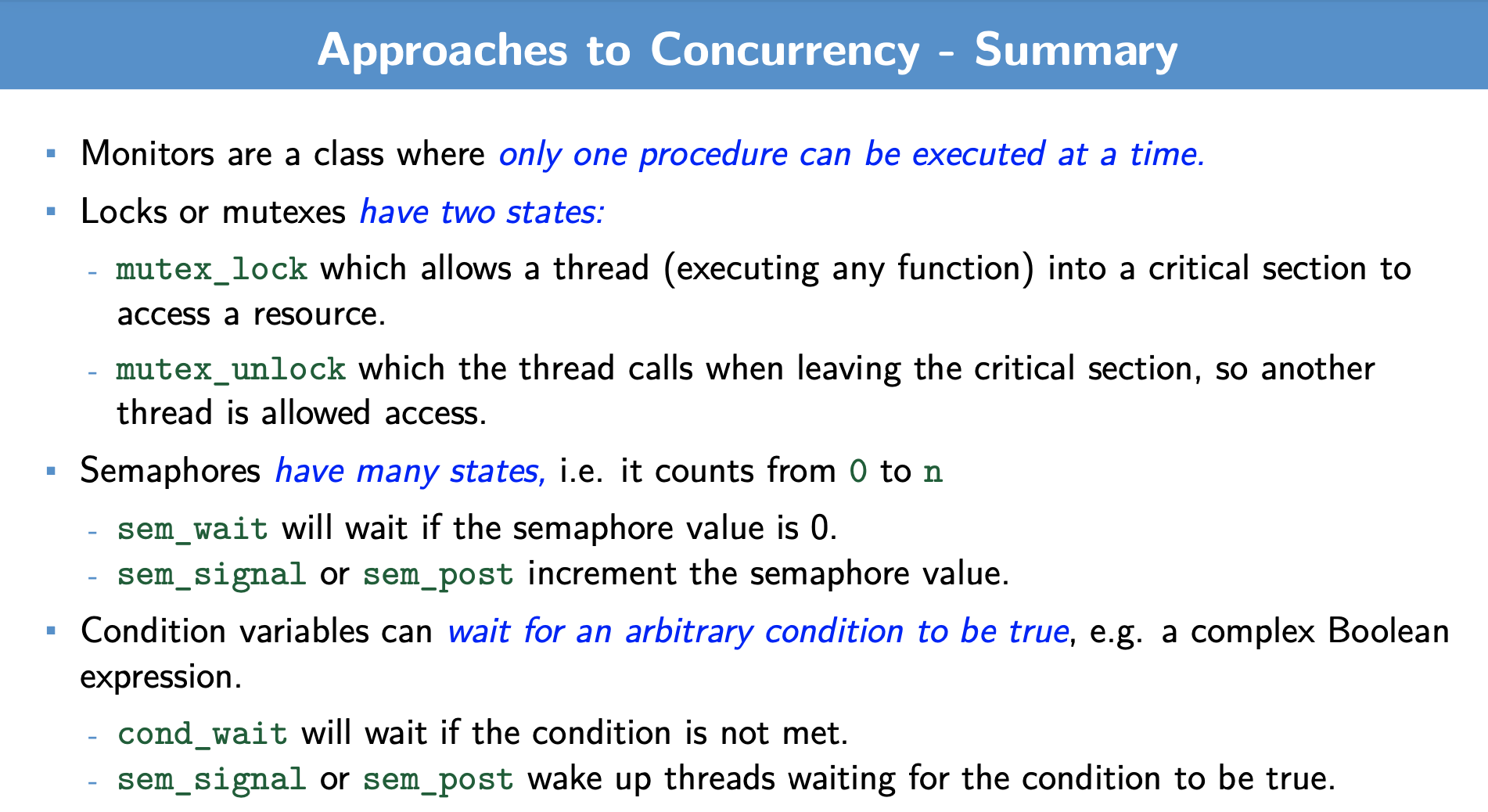

Monitors are a programming language construct (a practice/convention)

- essentially, it is a class where only one procedure executes at a time

- possibly less error prone than raw mutexes, but less flexible too. Below is an example:

monitor monitor-name {

// Shared variable declarations

procedure P1 (...) {

// Procedure P1 code

...

}

// ... Additional procedures

procedure Pn (...) {

// Procedure Pn code

...

}

Initialization code (..) {

// Initialization code

...

}

}- Can implement a mutex with a monitor or vice versa.

-

But monitor alone doesn’t give you condition variables.

-

Need some other way to interact with scheduler.

-

Use conditions, which are essentially condition variables.

-

So, how are Monitor’s implemented? They are often implemented via the things we have learned so far:

-

Mutex (lock): used for mutual exclusion — low-level synchronization primitive that ensures only one thread can hold associated lock at a time. The mutex is used to protect access to the shared data or critical section within the monitor.

-

Condition Variables: Monitors include condition variables, which allow threads to wait for a specific condition to be satisfied.

-

Entry Queue: Monitors maintain an entry queue associated with the mutex. This queue contains threads waiting to acquire the monitor lock and enter the critical section.

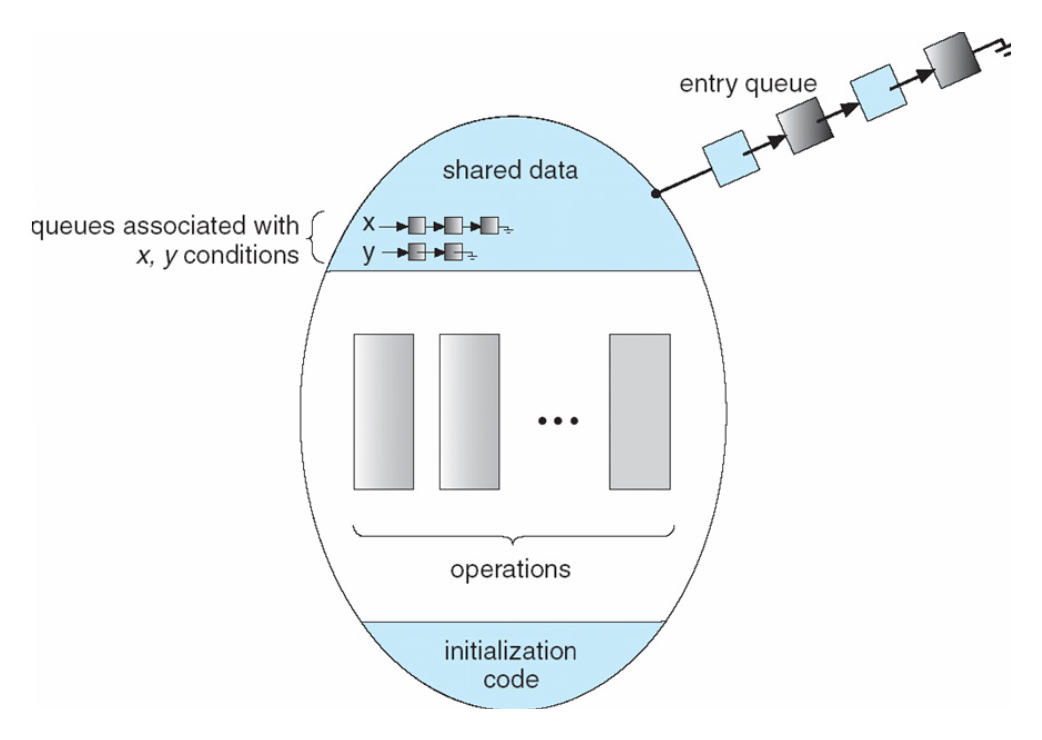

Consider the following visual:

Consider the following sequence of events:

- Thread Waiting on a Condition:

- A thread, let’s call it Thread A, enters the monitor and finds that a certain condition is not currently true (e.g., a shared variable has not reached a desired value).

- Release the Monitor Lock and Wait:

- Thread A releases the monitor lock and enters the condition queue associated with the condition it’s waiting for.

- Other Threads May Execute:

- While Thread A is waiting in the condition queue, other threads may execute procedures within the monitor, potentially changing the shared state.

- Signal or Broadcast:

- Eventually, another thread (Thread B) might execute a procedure that makes the condition Thread A is waiting for true. Thread B then signals or broadcasts on the condition variable associated with the condition.

- Thread A Wakes Up:

- Thread A, which was waiting in the condition queue, wakes up and moves from the condition queue to the entry queue. It is still waiting to acquire the monitor lock.

- Acquire the Monitor Lock:

-

When the monitor lock becomes available (for example, if another thread holding the lock releases it), Thread A acquires the monitor lock and moves from the entry queue to the critical section.

-

Where each thread, is running one method of the Monitor class. The monitor also encapsulates resources into its structure, as it encapsulates the management of shared resources. For the above, one way to implement the entry queue is to use a spinlock — which is a simple form of locking mechanism where a thread repeatedly “spins” or loops in a busy-wait manner until it acquires the lock. So, the top element of the entry queue continually polls to see if the lock is available.

We now take a look a semaphores, which are a entities that provide us more advanced locking mechanisms.

Semaphores

A semaphore is a synchronization primitive that is used to control access to a shared resource in a concurrent, multithreaded, or multiprocess environment. It was introduced by Edsger Dijkstra and serves as a generalized version of a mutex (mutual exclusion) and can also be used for inter-thread or inter-process communication — that is, while both semaphores and mutexes provide a way to control access to critical sections and synchronize threads, semaphores offer more flexibility by allowing a specified number of threads to access the critical section concurrently.

A Semaphore is initiazlied with an integer :

int sem_init(sem_t *s, ..., unsigned int n);There are 2 functions provided from this:

sem_wait(sem_t *s) // originally called P()

// If the semaphore value n is greater than 0, decrement it. Otherwise, wait until n > 0 and then decrement it.

sem_signal(sem_t *s) // sem_post in pthreads, originally called V()

// Increment the value of the semaphore by 1.Operation: sem_wait will return only n more times than sem_signal called. Instead it will wait until sem_signal is called again.

Example: If n is 1, then semaphore is a mutex with sem_wait as lock and sem_signal as unlock.

-

Semaphores give elegant solutions to some problems.

-

In the following slide, semaphores replace count in the Producer / Consumer problem.

-

Recall that count had to be between

0andBUFFER_SIZE. -

emptycounts how many spots are available (i.e. how empty it is) and the producer has to wait if there are 0 empty spots available. -

fullcounts how many spots have items (i.e. how full it is) and the consumer has to wait if there are 0 items available. -

The code assumes only one producer and one consumer otherwise you would need to protect the reading and writing of in and out by mutexes.

Here is the code:

// Initialize full semaphore to 0: block consumer when buffer is empty.

// Initialize empty semaphore to BUFFER_SIZE: block producer when queue is full.

void producer(void *ignored) {

for (;;) {

item *nextProduced = produce_item();

sem_wait(&empty);

buffer[in] = nextProduced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

sem_signal(&full);

}

}

void consumer(void *ignored) {

for (;;) {

sem_wait(&full);

item *nextConsumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

sem_signal(&empty);

consume_item(nextConsumed);

}

}

Benign Race Conditions

- Sometimes, allowing for race conditions provides for greater efficiency. For example, in cases where there is more focus on speed than accuracy:

- i.e you are looking for an approximate-not an exact-answer

- When you know you can get away with race condition. Consider the following code:

if (!initialized) {

mutex_lock (m);

if (!initialized) {

initialize();

initialized = 1;

}

mutex_unlock (m);

}- Cheap Check for Initialization:

- The first line checks if the variable

**initialized**is false. This is a cheap operation as it doesn’t involve acquiring a mutex. If**initialized**is true, it suggests that the initialization has already happened, and there’s no need to proceed further.

- The first line checks if the variable

- Locking the Mutex:

- If

**initialized**is false (indicating that initialization may not have happened or may be in progress), the code proceeds to lock the mutex (**mutex_lock(m)**). - Locking the mutex is a more expensive operation, as it involves acquiring a lock that ensures exclusive access to the critical section.

- If

- Double-Check for Initialization:

- After acquiring the mutex, there’s another check for

**initialized**. This double-check is necessary because another thread might have acquired the mutex and completed the initialization before the current thread.

- After acquiring the mutex, there’s another check for

- Initialization Routine:

- If the double-check confirms that

**initialized**is still false, the actual initialization routine (**initialize()**) is executed. This routine likely sets up some shared resources or performs other one-time setup tasks. - After initialization, the variable

**initialized**is set to true to indicate that the initialization has been completed.

- If the double-check confirms that

- Unlocking the Mutex:

-

Finally, the mutex is unlocked (

**mutex_unlock(m)**), allowing other threads to potentially acquire the lock and check or perform the initialization.

-

So in the above, a race condition may have occurred, where after the first !initialized check, the value is changed. But as that operation is inexpensive, we can check again after acquiring the lock (we do pay the price of locking the mutex)

So, how can we detect data races? We introduce Lockset algorithm — for detecting data races and ensuring the correctness of concurrent programs. It is particularly effective given:

-

For each global memory location, maintain a lockset (set of locks)

- e.g. the vector (1,1,1,1) if there are 4 locks in all

-

On each access of a particular global memory location, say

total, note any locks that are not currently held- e.g. if only locks 0 and 2 are being held at that time, the vector becomes (1,0,1,0)

-

If the

locksetbecomes empty (0,0,0,0) → there is no mutex protecting this memory location -

This approach is simple and it catches potential races even if they haven’t yet occured.

Sychronization: Motivation

Amdahl’s Law guides the effeciency gains when using multiple cores. Consider the equation:

-

Amdahl’s Law is a principle that expresses the potential speedup of a parallel algorithm or program when running on multiple processors. In the above, we have:

- : the time one core takes to complete the task

- : the fraction of the job that must be serial (fraction of job that cannot be parallelized)

- the number of cores

-

Suppose were infinity → Amdahl’s law places an ultimate LIMIT on parallel speedup. That is, there is an upperb bound as to how much multithreading can improve performance.

Synchronization increases serial section size. That is to say, synchronization increases the amount of code that cannot be run in parallel. So while it is essential for ensuring correct and predictable behaviour in concurrent programs, it can also introduce bottlenecks and reduce the effective parallelism by increasing the size of serial actions.

Locking Basics

Consider the following bit of code:

pthread_mutex_t m;

pthread_mutex_lock(&m);

cnt = cnt + 1; /* critical section */

pthread_mutex_unlock(&m);-

Only one thread can hold a lock at a time. I.e. if two threads call

pthread_mutex_lockthe function will return immediately for one of them and the other will block (i.e. wait). -

This function makes the critical section atomic by allowing only one thread at a time to increment

cnt. -

When do you need a lock?

- Anytime two or more threads touch data and at least one writes.

-

Rule: Never touch (global) data unless you hold the right lock.

Now, let’s look 2 methods of locking: (1) fine-grained locking and (2) coarse-grained locking:

struct list_head *hash_tbl[1024];

mutex_t m;

// Coarse-grained Locking

// Single lock for the whole hash table

mutex_lock(&m);

struct list_head *pos_coarse = hash_tbl[hash(key)]; // Walk list (iterate through the linked list) and find entry

mutex_unlock(&m);

// Fine-grained Locking

mutex_t bucket[1024]; // Separate lock for each linked list

int index = hash(key);

// Acquire lock for the specific bucket

mutex_lock(&bucket[index]);

struct list_head *pos_fine = hash_tbl[index]; // Walk list and find entry

mutex_unlock(&bucket[index]);In the above, we have hash table using separate chaining to handle collisions. So:

-

coarse-grained locking → one lock for the entire data structure (one lock for entire hash-table)

-

fine-grained locking → one lock for each of the elements of the data structure (for each LL entry in the hash-table)

What are the advantages and disadvantages for each respective approach?

-

Coarse-grained locking makes the most sense if the data structure is not used that often since it uses less space and less complexity as the thread only has to acquire one lock.

-

Fine-grained locking makes the most sense if the data structure is being used often and maximizing concurrency and performance is the goal.

- Fine-grained locking could also require a thread to acquire many locks to perform a task, which would slow it down.

-

A general approach is to identify areas where there is a lot of contention (threads often waiting for a particular resource) and use fine-grained locking in those areas.

Hardware-specific Synchronization Instructions

So, we’ve seen how important Mutexs are, and the various roles they play in multi-threading environments. We will look at how to implement a mutex function atomically using hardware-specific sychronization instructions — for x86-64 (x64) architecture:

The mutex implementation uses a common technique known as “test-and-set.” Here’s the snippet of code:

cCopy code

while (*mutex == true){}; // Test if mutex is held

*mutex = true; // Set it to true- The

**while (*mutex == true){};**line checks if the mutex is currently held. If it is, the thread enters into a busy-wait loop, repeatedly checking the value of the mutex until it becomes available (i.e.,**mutex**is**false**). - Once the mutex is determined to be available, the critical section is entered, and

**mutex**is set to**true**, indicating that the mutex is now held.

x86-64 Atomic Operation:

The x86-64 architecture provides an atomic operation called **xchg**. The **xchg** instruction is used to swap the value stored in a register with the value stored at a specified memory address. The syntax is:

assemblyCopy code

xchg src, addr**src**is a register that holds a value.**addr**is the memory address where the value should be swapped with the contents of**src**.

Application to Mutex Implementation:

In the context of mutex implementation, the **xchg** instruction can be utilized to perform the test-and-set operation atomically. For example:

assemblyCopy code

xchg eax, mutexThis instruction would atomically swap the contents of the **eax** register with the value stored at the memory location specified by **mutex**. Last lecure, we saw that x64 processors provide an atomic operation used to implement synchronization primitives such as mutexes, call xchg. Recall:

xchg— exchanges the value stored in a register with the value stored in main memory- The

**xchg**instruction is always considered locked, even without the explicit**lock**prefix. This ensures that the exchange operation is atomic.

- The

The rest can be found in Lecture 9. Given source register src and an address in memory addr, we can do xchg src, addr, which will swap the value stored in src with the value stored at address addr. With this in mind, we can implement mutex functionality:

mutex_lock(bool *mutex) {

while (xchg(mutex, true) == true) {}; // test and set, this is usually implemented via inline assembley

}

// there is extra logic above -> xchg swaps, and returns true if the value of *mutex has not changed

mutex_unlock(bool *mutex) {

*mutex = false; // give up mutex

}truemeans the mutex (and the critical section) is locked, andfalsemeans unlocked- If

xchgreturnstrue, then the mutex was already set and you have not changed its value → continue to busy-wait - If

xchgreturnsfalse, then the mutex was free and you have changed its value totrue→ you have just locked the mute (swap true with value of mutex, effectively locking it) - This construct is known as a spinlock since a thread busy-waits (loops or spins) in

mutex_lockuntil it is available.

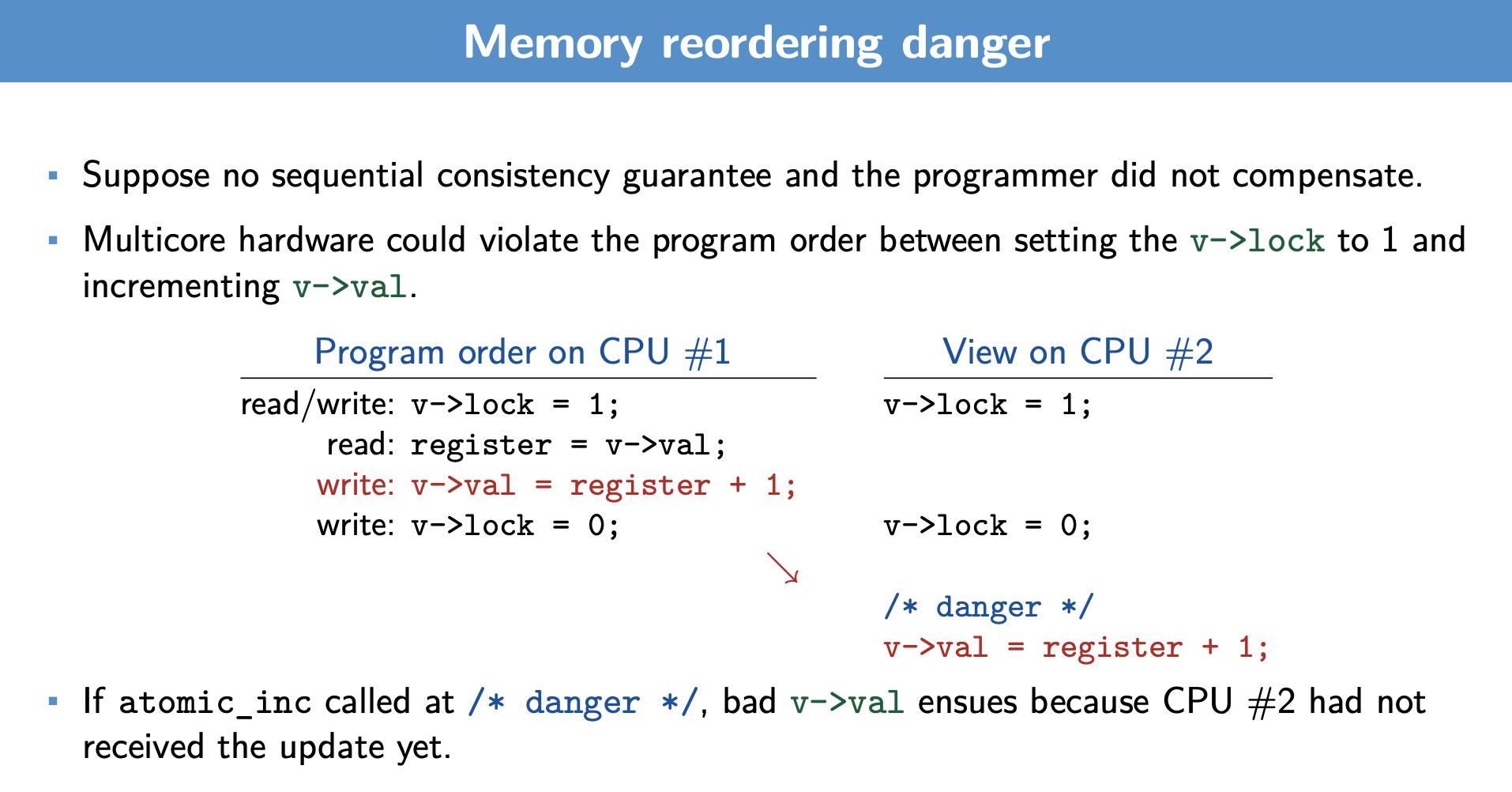

We know that the compiler likes to re-order to increase hardware efficiency. But, what are some risks in the above? For the left slide:

-

The view of the program in one CPU may be different than what another CPU see’s

- the code me be re-ordered, as seen above, into a state where, we are working with critical sections outside the safety of locking mechanisms

- in the slide, this means our

v-valupdate may not be using the correct version ofregisteras we are operating outside of the lock, and in a time when another thread likely has the lock and is manipulatingregister

-

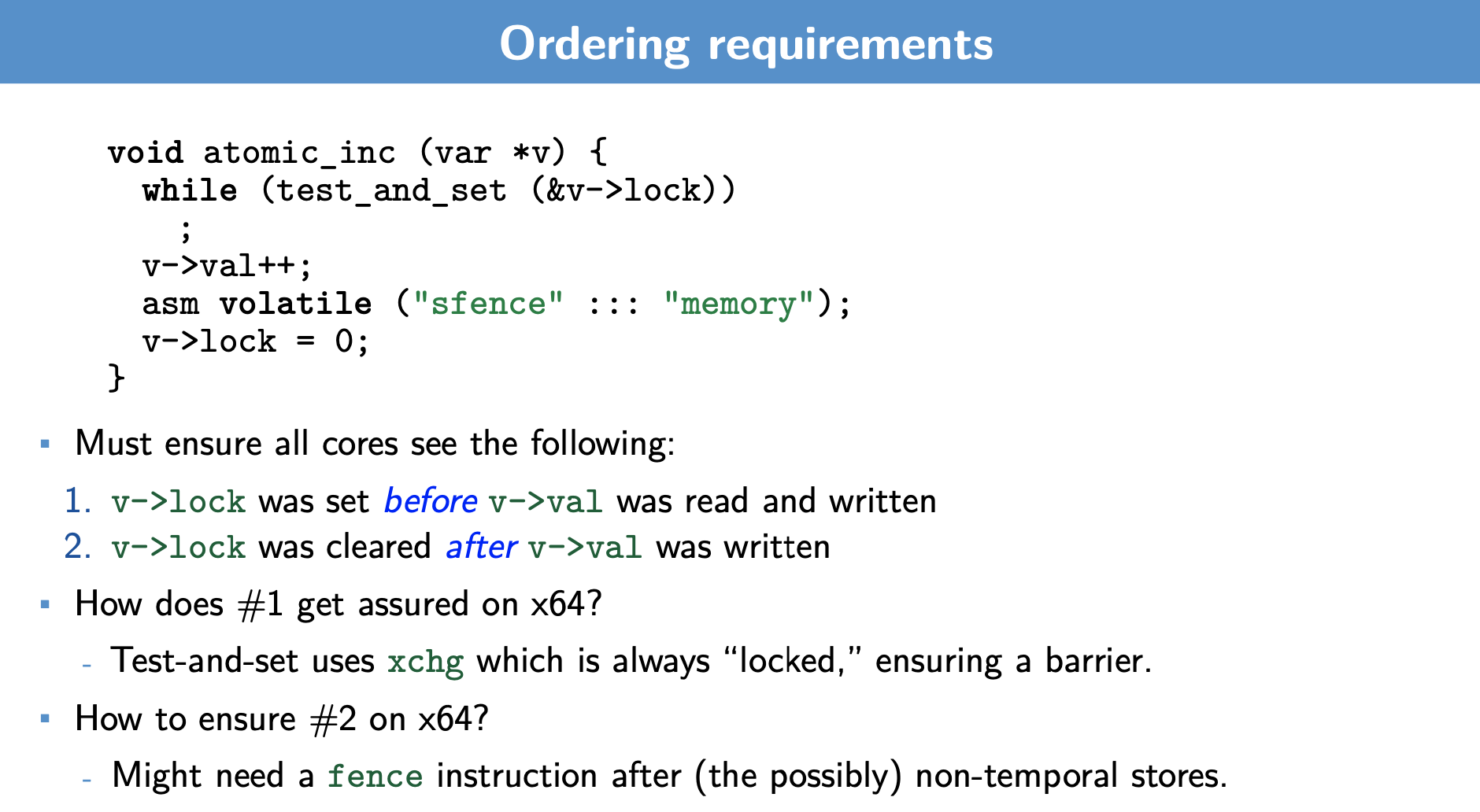

To address this, we need to ensure reads and writes occur within the lock, and in the order intendended. How?

-

The right slide addresses this

-

The bottom part:

asm volatile ("sfence" ::: "memory");

v->lock = 0 Is the unlocking phase. By doing so, we make it so that:

- As long as we have a lock and unlock on the top and after our critical section, we do not need the critical section to be atomic individually